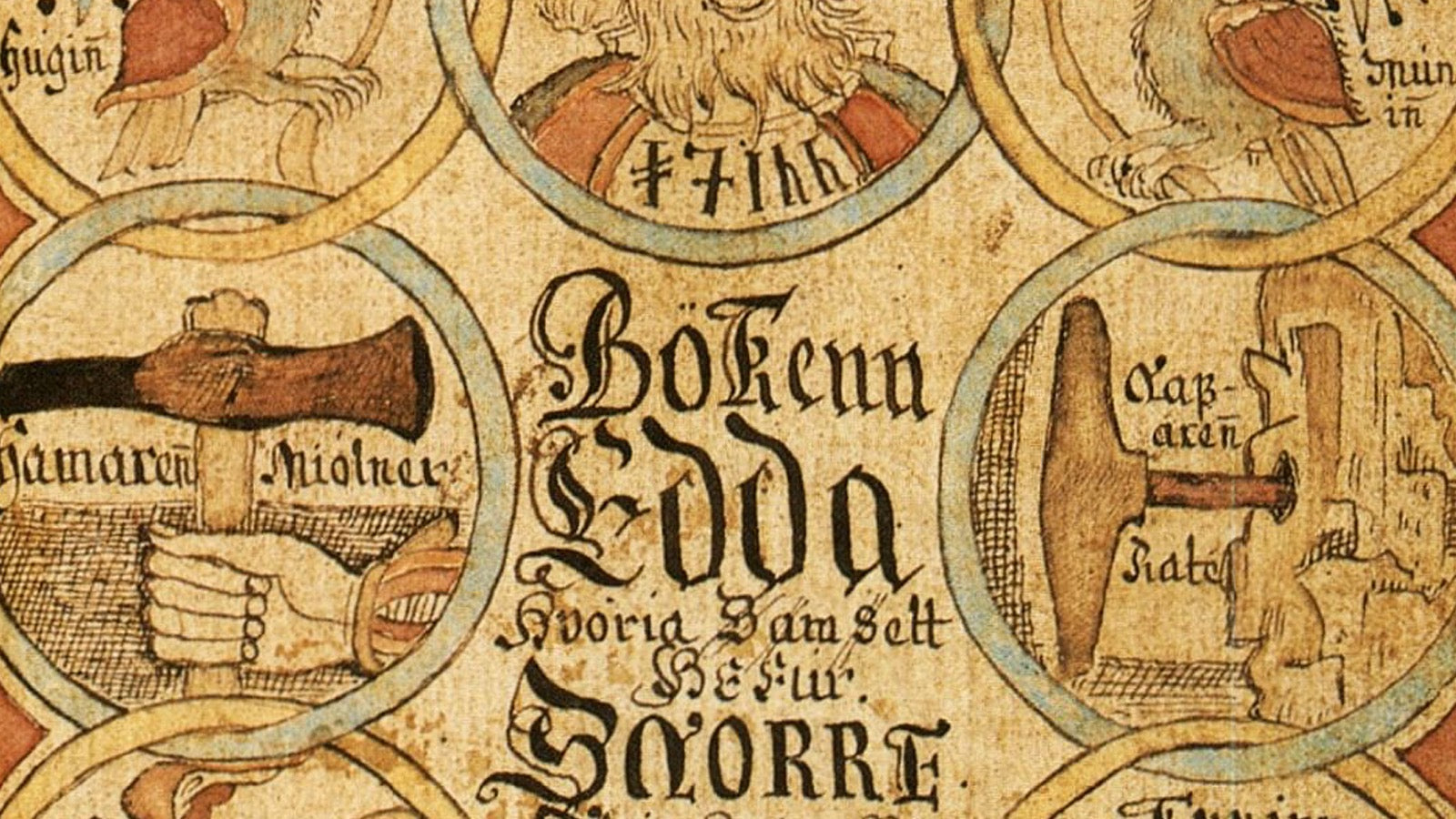

The Prose Edda

Even the casual student of Viking and Norse history will have stumbled upon the words “Prose Edda”.

What is the Prose Edda then? What can we learn from it? And why is it so important to understanding Norse history and culture?

Let’s dive in, and find out.

Written in the 13th century by Icelandic historian, writer and politician Snorri Sturluson, the Prose Edda is a fascinating study and one of the most impressive books to come from the middle-ages.

The work itself is divided up into four main parts: The Prologue, Gylfaginning, Skáldskaparmál, and Háttatal.

Many scholars agree that the contents of the prologue and the reason it was included in the first place was because of the religious and political climate in which it was written. At the time, in Europe, there was little tolerance for belief outside the mainstream; and Iceland was no exception.

This provides an explanation for the unique and pseudo-historical interpretation of the origin of the Gods as being wanderers from ancient Troy. At the very least, it would have given Snorri protection from repercussions for writing stories of the Gods.

The next section, Gylfaginning, or “The Tricking of Gylfi”, dives right into the stories of the Gods. We follow an ancient king of Sweden, Gylfi, who, after being tricked by one of the Æsir, decides to seek them out and learn more about them. On his journey to Asgard, he is spirited away by the Æsir to a great hall in which he meets Hárr, Janhárr, and Thridi (High, Just as High, and Third), all names for Odin.

Throughout Gylfaginning, these figures, Odin, and Gylfi, ask each other questions, and give answers to the history of the Æsir, the foundations of the world, the feats and travelings of the gods, all the way to Ragnarök, and the end of the nine realms as we know them. In fact, many of the tales you’ll read on this blog come from this section!

In Skáldskaparmál, (“the language of poetry”), another discourse is opened, this time between Ægir, a jötunn and deity of the sea, and Bragi, the god of poetry. The two discuss more or less the rules of skaldic poetry, giving examples, definitions, and a list of kennings (poetic versions of nouns).

This section provides fantastic insight into original Viking era skaldic poetry, things that were actually spoken and sung during that time, and provides a kind of handbook for skalds of the future to do the same.

The last section, Háttatal (“list of verse-forms”) is Snorri putting these past sections into practice. In it, he composed poetry and verse using the rules, examples, and prose illustrated in the former sections; giving the reader an example of how to put into practice what we’ve been talking about, with the caveat that these are open to interpretation.

If one wants to learn about the Vikings, their way of life, and particularly their culture, and belief, the Prose Edda is indispensable.

While other records exist, the edda is perhaps the most complete, and widely available record, and makes available the methods in which the Vikings and ancient Norse themselves learned these stories.