The Ouroboros Across Different Religions and Mythologies: Norse Legends and Beyond

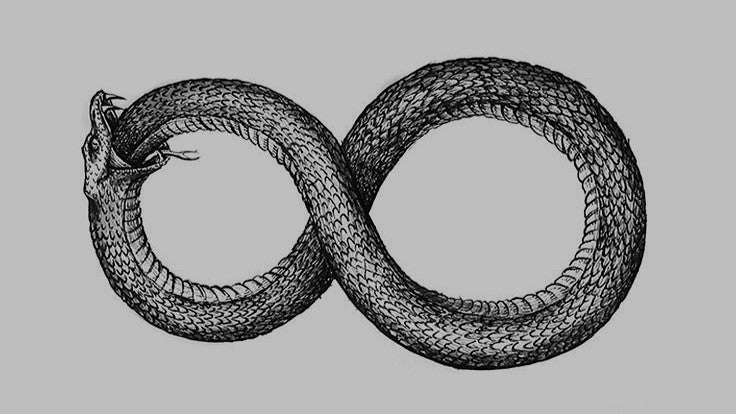

The Ouroboros—an ancient symbol showing a serpent devouring its own tail—has existed across cultures for centuries. While many might know it as a representation of cycles like life, death, and rebirth, in Norse mythology and Viking culture, it holds deeper layers of meaning. For those who revere Norse mythology as more than just ancient stories, understanding the symbol’s presence across various mythologies adds another layer of spiritual reflection.

1. Norse Mythology: Jörmungandr, the Midgard Serpent

In the Norse cosmology, the Ouroboros is closely related to Jörmungandr, the colossal serpent that encircles Midgard (the realm of humanity). Jörmungandr is one of the children of the god Loki and the giantess Angrboða. He is often depicted gripping his own tail, completing a perfect circle around the world. This visual evokes the Ouroboros and carries the profound theme of balance between creation and destruction.

According to prophecy, Jörmungandr’s existence is tied to Ragnarok, the great battle that will reshape the world. The serpent's endless loop around Midgard serves as a reminder that even in chaos, there is order—a balance of forces. His battle with Thor, the god of thunder, signals the end of one age and the start of another. This notion of cycles aligns with the Ouroboros symbol, making it a natural fit for those who honor Norse beliefs.

2. Ancient Egypt: The Cosmic Ouroboros

The Ouroboros made one of its earliest appearances in ancient Egyptian mythology, where it symbolized the universe's cyclical nature. The serpent was often associated with Atum, the creator god, and Ra, the sun god. In Egyptian belief, the Ouroboros represented the eternal return of the sun and the unending cycle of birth, death, and rebirth.

One notable depiction is found in the Enigmatic Book of the Netherworld, where the Ouroboros encircles the solar disk, signifying the unification of opposites—life and death, day and night. The ancient Egyptians also connected the Ouroboros to Mehen, a serpent deity who protected the sun god Ra on his nightly journey through the underworld.

3. Greek and Gnostic Traditions: A Symbol of Alchemy

The Greek version of the Ouroboros often appears in Gnostic and alchemical texts, where it is associated with the concept of unity in duality—the merging of opposites such as life and death, heaven and earth, and the conscious and unconscious mind. In alchemy, the Ouroboros represents the process of transformation, the idea that destruction leads to creation, much like the purification of base metals into gold.

The Gnostic sects viewed the Ouroboros as a symbol of the material world's impermanence. It conveyed the belief that the material realm is a self-contained loop of endless repetition, trapping the soul until it attains spiritual enlightenment and breaks free from the cycle.

4. Hinduism: The Cycle of Samsara

While the Ouroboros itself may not appear in Hindu iconography, its themes resonate deeply with Hindu beliefs surrounding Samsara—the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth. This cyclical view of existence is central to Hindu philosophy, which teaches that the soul (Atman) reincarnates in various forms until it achieves Moksha, or liberation from the cycle.

In this context, the Ouroboros can be seen as a representation of Samsara, where life feeds into death, and death into life. The symbol resonates with Hindu cosmology, where time is seen as cyclical rather than linear, stretching across vast cosmic epochs known as Yugas.

5. Aztec Mythology: The Serpent of Creation

The Aztec culture had its own version of the Ouroboros in the form of the god Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent. Although Quetzalcoatl is not depicted consuming his tail, he embodies many of the Ouroboros' themes, such as creation, destruction, and rebirth. In Aztec mythology, Quetzalcoatl was responsible for creating humanity and was associated with the cycles of the earth and the heavens.

The Aztecs believed that the universe was created and destroyed multiple times, each ending with a cataclysmic event. Quetzalcoatl's role in these cycles of creation and destruction aligns closely with the Ouroboros' symbolism of continuous renewal.

6. Christian Mysticism and Medieval Europe: The Eternal Return

In Christian mysticism, the Ouroboros was sometimes used to symbolize eternity and the idea of God as the Alpha and Omega—the beginning and the end. The serpent devouring its own tail was interpreted as a symbol of God's infinite nature and the eternal life promised in Christian theology.

During the medieval period in Europe, the Ouroboros appeared in alchemical manuscripts, where it symbolized the unity of the spiritual and material worlds. Medieval scholars viewed the symbol as representing the idea that life is a continuous process of spiritual transformation, with the end goal being the reunification of the soul with the divine.

The Ouroboros serves as a symbol of eternal cycles, not only in the distant past but in the living traditions of those who follow Norse beliefs today. Whether reflected in the serpent Jörmungandr or in other cultures' depictions, the Ouroboros speaks to the eternal cycles of creation, destruction, and rebirth. For modern followers of Norse spirituality, this ancient symbol resonates with the way we view the universe—a constant interplay of forces, ever moving, yet always connected.

At its core, the Ouroboros reminds us that every end is a beginning, and every beginning is part of an endless journey—just as Jörmungandr’s great coil encircles Midgard, balancing order and chaos.